Article: Hip Hop Cinema – New Jack City

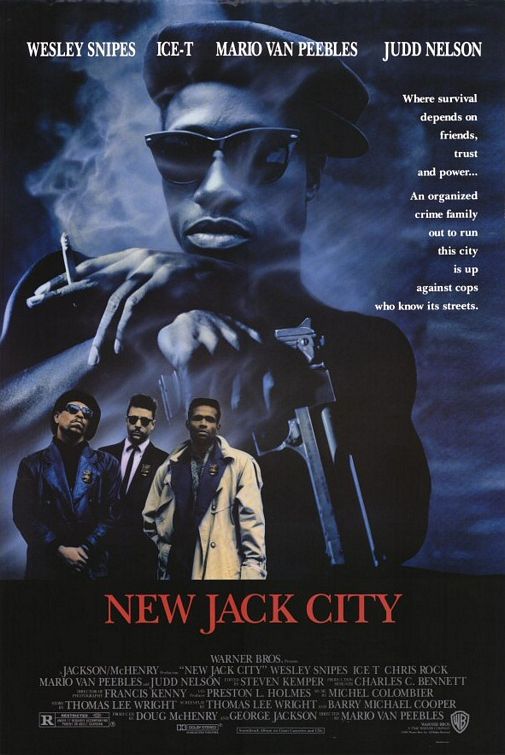

1991’s ‘New Jack City’, a formulaic story of drug kingpin (Wesley Snipes) and the undercover cop trying to take him down (Ice-T), may feel like digging into a time-capsule of music, fashion and social ills, but it also paints a subtle picture of the musical tug of war circa 1990 between counter-culture Rap and its commercial cousin New Jack Swing.

‘Hip Hop Cinema’ is a series of columns delving into the history of hip hop culture in cinema and television.

1991’s New Jack City, a formulaic story of drug kingpin (Wesley Snipes) and the undercover cop trying to take him down (Ice-T), may feel like digging into a time-capsule of music, fashion and social ills, but it also paints a subtle picture of the musical tug of war circa 1990 between counter-culture Rap and its commercial cousin New Jack Swing.

The early 90s is a rich period for films delving into African American urban culture. So while Spike Lee and the like were making richly textured social commentary, Mario Van Peebles’s directorial debut instead delivers a straight-up genre film bordering on Blaxploitation, becoming the highest grossing independent film for the year of its release. Peebles’ approach is far from subtle, especially when dealing with such a complex problem like drug abuse in urban American, but his fervour and earnestness is so well intentioned that its possible to forgive its clumsiness. Which is not to say the filming is incompetent, as many of the action scenes are very well done (particularly the sequence where Ice T’s cops raid a heavily populated crack den).

In terms of plot, New Jack City doesn’t provide much surprise. Set during the crack epidemic in New York City, mid-80s, we see the rise to power of a ruthless young crack dealer Nino Brown (Wesley Snipes) and his highly disciplined gang, while undercover cops Scotty (Ice-T) and Peretti (Judd Nelson) try to infiltrate the group with the help of former crack-head Pookie (Chris Rock). The charismatic young star Wesley Snipes really dominates, generating an intense and imposing screen presence as a truly magnificent bastard, while supporting roles from Allen Payne (who of course starred alongside Chris Rock in CB4, discussed last week), Bill Nunn and Mario van Peebles flesh out a fine cast which struggles with some pretty standard material.

Snipes’ Nino Brown is no Scarface, and the characters make a point of referencing it several times in the film to prove it. Snipes isn’t a tragic figure corrupted by power, instead he’s a highly intelligent young businessman with no compunction about abusing the poor and disenfranchised to make himself a quick buck, meanwhile talking a big game about social injustice and economic inequality to excuse himself. When later in the film he uses a 4-year-old girl as a body-shield and executes one of his closest friends, it’s purely business.

His foil is Ice-T’s Scotty, here in his acting debut, plays a surprisingly small role, helping Chris Rock’s character kick his cocaine habit, and in general sneering a lot. Later he infiltrates Snipes’ gang, but the two don’t get enough scenes together to quite sell it. Ice-T of course would go on to play quite a few gang-affiliated characters in his career, but his role here matches precisely the role he still performs on ‘Law & Order SVU’ as a former undercover narcotics officer.

What makes the film work is the subtle integration of music and fashion to flesh out the sense of place and the feeling of their world. New Jack Swing, now mostly forgotten as a genre, was hugely popular around 1990. Not quite hip hop, but borrowing elements of it, a vocals-based approach fusing drum machines with synthetic instruments and RnB and dance rhythms, the genre is a near constant fixture in the film’s soundtrack (here overseen by Michel Colombier, a name long familiar to soundtrack buffs). It almost functions as a Greek chorus, providing literal context to scenes, as in a scene where a New Jack Soul Quartet shiver and sing around a flaming barrel while we see a montage of Nino’s gang violently clearing out a housing tenement.

With the aide of hindsight, the casting of an idealistic Ice-T against a crew of cynical drug dealers mirrors the struggle between Rap and the popular genre of New Jack Swing in the development of hip hop. On the side of justice is Ice-T, working with the law but at odds with it. His whose own politics in his rap career match that of his character, who has fought hard to climb out of a gang background. If you want to be obvious about it (and I do), the undercover cop character is literally underground.

On the other side, once Snipes and his gang become entirely commercially focused, they rake in the dough, don jazzy new low-top fades with immaculate shaved hair designs and bright suits, and host big dance parties featuring New Jack Swing pioneer Teddy Riley, as well as Flava Flav and Fab 5 Freddy (also one of the film’s producers). All of the characters know that despite their big talk and their lavish spending, the gang believes in nothing except money. Its not an entirely fair or true assessment of the motives behind New Jack Swing (except perhaps from the point of view of hip hop purists), nor do I believe it was considered by anyone involved in the film’s production, but it’s a useful analogy to explain how the two disparate styles might have appealed to different ideals in the urban community in the wake of the Reagan era, and how genuine musical movements were co-opted by commercial music interests.

In real life the lines between the two musical styles would eventually become blurred, with New Jack swallowed up as a commercial pop fad, and Rap becoming a slick popular product in its place (as discussed in last week’s article about 1993’s ‘CB4’). The 90s genre film may seem quaint today, but ‘New Jack City’ at least is a cultural oddity which happens to still be entirely relevant today, maybe because it takes a popular approach to address real social concerns. That, and Wesley Snipes.

—

More Info / Soundtrack