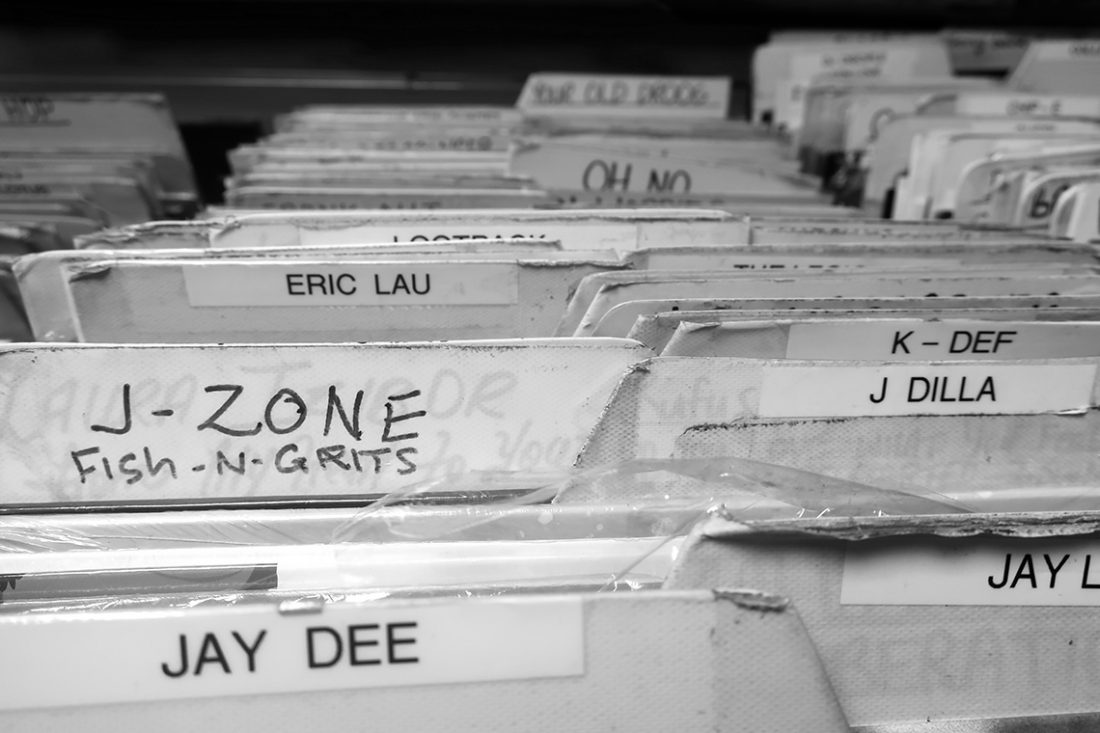

J-Zone (Interview & Photography)

Eternally restless and singularly driven, J-Zone is a lifelong scholar of beats, rhymes and life. From his earliest funk ambitions to forging his own path in hip hop before starting a second musical life outside of the confines of being a rapper, his career has moved with an enviable fluidity.

The Find last caught up with J-Zone in 2013 after the release of his book Root for the Villain – part memoir, part takedown of the music industry, part obsessive exploration of hip hop minutiae. There we found a man trying to figure out how his post-rap musical life would look, impatient with the annoyances of city life and anxious to find a new path.

Fresh from rehearsal with a drum stool under his arm, the J-Zone I sat down with was calm and motivated. He’s found a new path and that restless energy has been redirected into the pursuit of a new perfection, but first we looked backwards to where it began.

(Photography: Cindy Baar | Words: Emily West)

I hear you had a pretty interesting apprenticeship in hip hop from a young age. Can you tell me a little about that?

I hear you had a pretty interesting apprenticeship in hip hop from a young age. Can you tell me a little about that?

That was my first experience both of the music business and with interacting with people in that professional way. It was basically getting information and education for free, way before there were schools for that type of music production. The size of the studios then was so different to now, the scale was unreal. That time also taught me a lot about professionalism.

Many rappers would book studio time and not turn up. You’d hear these stories in magazines about them beefing with their labels but I’d know that some of these guys had not turned up to their studio time, or turned up and just partied… When I’m in the studio now it’s all about professionalism. Though I work a lot from my home studio now.

And what do you use as a home studio setup?

I’m not a big fan of technology, I just like to use what it takes to get things done. So I have the oldest model of Pro Tools that there is… Pro Tools 6.2. I have a few different drum kits, I’m a big fan of vintage drums so I have two old kits from the 60s that I love, and then I have some snares and things like that. I also have a bunch of cheap microphones.

When I see people trying to achieve the kind of sound that comes across on old sampled records, and they’re talking about how you need this 1965 Neve SSL console that costs about 9 million dollars and you need this one microphone that The Beatles used that costs 8 million dollars… I’m like, who can afford that?

“Really, my studio is a piece of shit. I love it, but there’s very little expensive gear there”

So what I did was I experimented, and with a lot of trial and error I was able to get a nice unique sound and spend almost no money. Really, my studio is a piece of shit. I love it, but there’s very little expensive gear there. I subscribe to the theory that the tools don’t make the carpenter, it’s how you use what you have.

When you go in to record, and when you’re picking up equipment – say at a garage sale or whatever – are you looking for a particular sound or is it a case of playing with the equipment and letting those idiosyncrasies shape the sound?

A lot of it is a guess, a crap-shoot. Like, you might talk to other people who are into old equipment, and companies that I like. So say if I find an old piece of TASCAM gear, I’ll pick that up. When it comes to microphones I like Electro-Voice, their mics don’t all sound exactly the same but they make a lot of cheap dynamic mics that I like. When it comes to musical instruments… I’ve had probably fifteen different drum sets and over 20 snares drums. I like old Gretsch drums, old Sonor drums, old Premier drums, old Camco drums…

A lot time the tuning and the heads and the wires that you use, the way you set the drum up, matters more than the drum itself. I alter a lot of my drums, I’ll take the hoops off of one and put them on another. I’ll try different ways to treat the drums – I’ll use tape sometimes, I’ll use felt, I’ll use those Dr Scholl pads. I’ll just experiment until I get the sound I like.

I know that you came up as a drummer and a bass player, and you talk about your sound a lot from a drummer’s perspective. Is your recent move away from hip hop shaped by moving more towards the drums?

I know that you came up as a drummer and a bass player, and you talk about your sound a lot from a drummer’s perspective. Is your recent move away from hip hop shaped by moving more towards the drums?

When I was a young kid I was a bass player first and foremost, but the problem was that I couldn’t find seven other guys to start a band with. I’d noticed that in listening to hip hop, all of the samples were basically what I was practicing bass to. I thought maybe I could do that instead, I wouldn’t need a band, I wouldn’t have to depend on people… I could do it all by myself.

“I got known as a rapper but I never considered myself to be one. I used to love making hip hop albums but I hated being a rapper”

Hip hop turned out to be how I made my name and got around the world and met all these people. But eventually it reached the point where I didn’t like the business of hip hop, I got known as a rapper but I never considered myself to be one. I used to love making hip hop albums but I hated being a rapper. So I got frustrated. I think that if you love to do something and walk away from it because you’re not making money or it’s not succeeding then to me that’s quitting, but if you walk away from something because the passion just isn’t there anymore then it’s moving on.

That’s what happened to me, I always loved hip hop for what it is and I’m proud of what I’ve done, I still listen to a lot of the records that I grew up on and stuff, but I just didn’t have any desire to continue being a hip hop artist.

So, what was next for you after moving on?

So, what was next for you after moving on?

In order to fulfill the musical thirst that I had, I had to do something, and something about drums was just calling me. I was watching a lot of old videos of James Brown’s drummers and old jazz drummers like Elvin Jones and Max Roach that made drums seem like such a cool instrument. I took this really disciplined approach of practicing 5-6 hours a day for years and I was able to make auditions and get into a few bands and then when I started incorporating those drumming skills into my production it made me want to make rap records again.

But still, then it came to the time to question whether I was going to continue to make rap records and just not tour, because I was never doing shows. So right now I’m a DJ, I play drums and I produce. I’m able to just be about the music, I don’t have to be a persona. If I was a rapper then I’d have to get into controversy before every album because I’d have to sell it. So I’d have to go on Twitter and diss somebody or I’d have to go and hit somebody in the head with a bottle of beer the week before the album comes out.

How did you feel as a rapper, not being a major-label artist but also not fitting into the indie philosophical clique?

How did you feel as a rapper, not being a major-label artist but also not fitting into the indie philosophical clique?

There was nowhere for me to go. On the indie rap scene when I came out, say 1999-2000, it was all about being lyrical-lyrical-lyrical. Everything was a punchline and it’s all about battling, releasing 12 inch singles and just talking about rap. Rapping about rapping. If you weren’t doing that you were being really ultra-conscious to the point of beating your audience around the head. Then of course there’s all the drugs, money and hoes rapping in the commercial world. Everywhere I went, people just didn’t like me.

I remember opening up for Atmosphere once and some of his fans were coming up to me after the show and just screaming at me. These girls would just scream at me and I was like damn, it’s only a joke. I’d be on bills with rappers who were more conscious and they would look at me like I was a clown and a joke and then it still wouldn’t work with rappers who were more battle and more street.

“I don’t want to be relevant in hip hop. I want to be irrelevant in hip hop. I just want to make what I want to make for people who appreciate what I do.”

I just never really wanted to be a rapper to begin with. I just wanted to make rap records and never be seen. I didn’t want to do shows, I didn’t want to tour. I was only a rapper because I wanted to be a producer, but rappers are so unprofessional. I would book studio time and rappers wouldn’t show up. So I was like, I’m never going to be able to make records unless I rap myself. I loved making those records, I had a blast making all of my albums. The problem was that once the records were out I had to live up to being a rapper and I hated that.

I got into a rap career because I don’t want to depend on other people and I just want to make some really cool rap records and I’m happy that I got a chance to do that. But I have no interest in staying “relevant”. I don’t want to be relevant in hip hop. I want to be irrelevant in hip hop. I don’t want to be relevant in rap music at all, I just want to make what I want to make for people who appreciate what I do. That’s what I want to do.

Do you now feel like you’re far enough away from that to be able to put something out and not have people expect you to do what you used to do?

If I wake up tomorrow and want to make a rap record I can do that. I don’t have to feel like, I hope the blogs cover it, I hope that the radio plays it, I hope that people notice… I don’t care. I make the records for my enjoyment and there’s a very small but loyal following of people that go to my Bandcamp and buy every release. Those are the people that I care about.

The last five or six years of my life since the book came out have been about figuring out what to do, and setting up the second half of my life, as an artist, a musician and a person.

You obviously have a very varied musical background and skillset, and so do a lot of your collaborators. Can you tell me about how this all comes together?

So now I have The Du-Rites, The Zone Identity, I also play drums in rock bands, in a soul band and I have my weekly residency playing funk and soul records down at the Tuck Room and I have my RMBA column. I do a lot of studio drumming too, replays for people who can’t clear samples and studio drumming. I compose music for television as well. That’s my retirement plan, doing music for television that can be licensed, stuff with no samples in it.

All of these different drum gigs make me a better drummer through playing with all of these different musicians, with different tendencies. Also both of these bands have singers out front, so I can’t be back there doing solos and going crazy trying to be ultra funky, I’ve just got to keep time and keep everybody comfortable. It’s been a lesson in discipline, it’s been a lesson in being unselfish and listening to what people want, you have to learn how to take criticism. My ego had to take a hit and I had to step back and be humble. It’s totally different.

Who are your drum heroes, who guides you?

Who are your drum heroes, who guides you?

My drum heroes are Funky George Brown from Kool and the Gang, Bernard Purdie who really showed me the kind of discipline you need to be good. Joe Dukes who played with Jack McDuff who was a very underappreciated dude, a real monster. There’s certain drummers out there where you listen to them and either you want to quit or you want to put in that work to get to that point.

Clyde Stubblefield was the guy who made me want to play drums in the first place. Just watching him is what made me go out and buy a pair of drumsticks. When I saw him in action that’s when I knew I wanted to play drums. It made me not content to watch anymore, I never sampled a drum beat again. Instead of sampling I used that as inspiration to get good enough to just sample myself.

“I just want to have command of my instrument the same way that I had command of the MPC2000 or a pair of Technics 1200s”

And what keeps you going in this musical second life, what drives you?

Getting up every day and knowing that I could be better at what I do. Knowing that I’ve come a long way and that I basically changed careers and picked up a new instrument in my late thirties means that I’m so aware that there’s so much I don’t know. I’m never going to be Buddy Rich, I’m never going to be Travis Barker but I just want that command of my instrument, and the confidence to sit down and have command of my instrument the same way that I had command of the MPC 2000 or a pair of Technic 1200s.

I want to control the drums in the same way and knowing that I’m not there yet just gets me up every day so I can make better records, play better live shows, practice better, be a better listener and composer… We can all improve and be better and I want to keep improving until I can’t make music anymore.

That’s the motivation.

More:

More: